We’re Not Racing to the Moon, We’re Making It Home

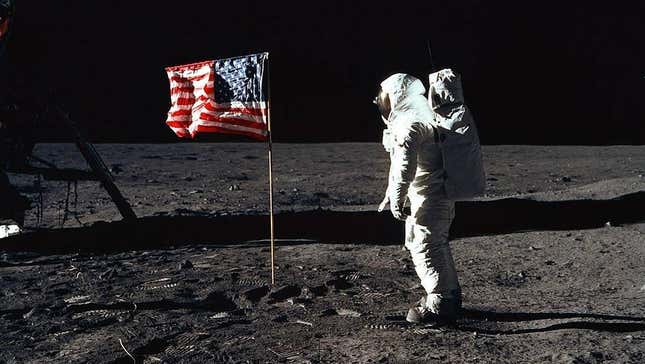

More than 50 years ago, the Apollo program was crafted as a result of rising political tensions between two competing nations. As a new group of countries and emerging space companies set their eyes on the Moon once more, they aren’t going back for national pride but rather to further their space ambitions beyond the celestial object.

In 1972, Eugene Cernan became the last astronaut to walk on the Moon when he stepped off the lunar surface as the commander of the Apollo 17 mission. Following a heated space race that lasted for roughly 20 years, things cooled off considerably for Earth’s natural satellite, as NASA sent rovers and orbiters to different parts of the solar system instead. More than four decades after Cernan’s dusty boot prints left an imprint on the cratered surface, however, a new race to the Moon is finally taking shape and the stakes are much higher this time around.

In case you haven’t been paying attention, the Moon is super hot right now (figuratively speaking, of course). This year alone, India became the fourth country in the world to land on the Moon by flying the first mission to the lunar south pole. The Moon also claimed a Russian lunar lander, which failed in its attempt to touchdown on its cratered surface. Four more lunar missions are planned for 2023, including a Japanese lunar lander and a commercial spacecraft by Houston-based company Intuitive Machines.

This renewed interest in the Moon goes far beyond the Cold War rivalry between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. Instead, it has more to do with establishing a long term presence on the lunar surface, with both public and private entities seeking to claim lunar resources and growing commercial interests in space. Rather than a race between two nations to plant a flag on the surface of the Moon, there’s a steady paced marathon towards establishing a lunar economy—one that has the potential to transform the most prominent celestial object in our night skies. It also has the potential to end America’s reign as the global leader in space.

Does a space race exist between the U.S. and China?

In the late 1950s, the U.S. and the Soviet Union competed over which nation had the technological means to land astronauts on the Moon. President John F. Kennedy insisted that the U.S. had to establish itself as a global leader in space exploration through his famous 1962 speech at Rice University, saying: “We choose to go to the Moon.” At the time, it was pretty obvious who was going to get to the Moon first.

“The Apollo Moon race was never actually close,” Christopher Impey, professor of astronomy at the University of Arizona, told Gizmodo during a phone interview. “America won that, Russia wasn’t really on the edge of getting there at that time.”

The first race to the Moon stemmed from a political context. “The new race has more players, different kinds of players,” Impey added. “And the context of the political rivalry is also different, replacing the America-Russia rivalry with America-China.”

In 2013, China became the third country ever to land on the Moon with its Chang’e-3 mission. The Chinese nation may have been late to the global space race but it has certainly made up for lost time. Since its first lunar touchdown, the country’s Chang’e-4 lunar probe became the first spacecraft in history to safely land on the far side of the Moon, which it did in January 2019. In December 2020, the follow-up Chang’e-5 mission returned samples from the lunar surface to Earth. The upcoming Chang’e-6 mission is scheduled to launch in May 2024, with plans to return samples from the Moon’s south pole.

China is aggressively advancing its lunar program, with plans to land astronauts on the Moon by the year 2030 and build a permanent base on the Moon. The International Lunar Research Station Moon base was announced as a joint project between China and Russia in 2021, and other countries, such as the United Arab Emirates and Pakistan, later joined in on the endeavor.

Although it was once the main contender to the U.S. in the space race, Russia has since fallen significantly behind. Russia’s attempt to land on the Moon’s south pole ended with a fatal crash on the lunar surface on August 19. “It’s not obvious what Russia brings to the table in its alliance with China, China is by far the major partner,” according to Impey.

China may be more advanced than most other countries in terms of its space program, but can it really take on the U.S. so late in the game? Jay Zagorsky, an economist at Boston University’s Questrom School of Business, has been looking at the numbers behind the space industry and noticed that the U.S. might be slipping.

The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, which tracks the nation’s gross domestic product, began monitoring the space economy from 2012 to 2021. The data revealed that space’s share of the U.S. economy is shrinking. Throughout those nine years, the space sector’s inflation-adjusted gross output grew an average of 3% a year compared with 5% for the overall economy.

Despite the increased talk of the space industry in the U.S. and the introduction of private companies, space is not growing as fast as other economic sectors. “If you just read the headlines, you’d think, ‘wow, space is doing amazing,’” Zagrosky told Gizmodo during a phone interview. “But as an economist, I’m like, ‘wow, space is doing terrible.’”

Earlier in July, the Senate Appropriations subcommittee responsible for overseeing NASA’s budget revealed its proposed NASA budget for 2024, allocating $25.4 billion towards the space agency. The spending bill grants NASA a slightly tighter budget than the $25.4 billion the agency received in 2023 and a significant cut from the $27.2 billion requested by the Biden Administration for the upcoming fiscal year.

Other countries may not have as much to spend on space, but they are increasing their space budgets over time. “The U.S. occasionally seems to be taking its foot off the gas,” Zagrosky said. “Yes, the U.S. has the world’s biggest space economy now but that lead is not assured.”

Private players of the space race

It’s not just nations racing to the Moon this time, however, as more commercial ventures elbow their way into the ongoing space race. Private companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin are teaming up with NASA to fulfill parts of its Artemis missions to the Moon. Once they get to the lunar surface, these private players have their own long term plans.

Related article: Beyond SpaceX: The Rising Stars of the U.S. Rocket Industry

“I suppose in some sense, you could think of this as a space race but it’s really a very different kind of space race than it was in the 1960s and 70s,” Jack Burns, director and principal investigator of the Network for Exploration and Space Science, told Gizmodo in a phone interview. “Today you’ve got individual private companies, all being able to put (uncrewed) landers at least on the Moon. The technologies have advanced and so it’s cheaper to do these things than we ever have imagined 50 years ago.”

Texas-based company Intuitive Machines is hoping to become the first private space venture to land on the Moon with its Nova-C lander, which is scheduled to launch in November. Intuitive Machine’s lunar lander has been in development since 2019, when NASA awarded the company a $77.5 million contract as part of the space agency’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services. Nova-C will carry five NASA payloads to the Moon’s surface and will operate for one lunar day, or 14 Earth days, spent collecting scientific data that may prove useful for future crewed missions to the Moon. Another private company, Astrobotic, is also preparing its own lunar lander as NASA’s commercial partner.

Delivering payloads to the Moon is just the initial phase. Increased access to the lunar surface for both robotic and crewed missions not only opens up opportunities for scientific research, but also allows for industrial utilization of the Moon by mining mineral resources or establishing lunar tourism.

In August, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) kicked off a seven-month study seeking ideas from private companies for technology and infrastructure concepts that could help build a Moon-based economy within the next decade. And earlier this year, a NASA scientist also revealed that the space agency plans to explore the potential for lunar mining within the next 10 years using a pilot processing plant to potentially extract resources such as water, iron, and rare metals.

“In a decade, two decades, I could see a number of private companies doing work on the Moon and having businesses that operate there,” Burns said. “We’re on this pathway and I think we’re going to continue.”

Aside from the commercialization of the Moon, the ongoing quest to return to the lunar surface also has to do with another object in the solar system. Future astronauts could use the Moon as a training ground to reach Mars, learning how to live and work in the habitat of another world.

Related article: Will Mining the Moon and Asteroids Be Worth the Trouble?

In that sense, the Moon is an important stepping stone towards Mars. “We’re learning how to do these things on the Moon, including exploration, mining, and surveying for resources, all of which are going to be needed to then continue the next step towards Mars,” Burns said.

Are we fighting for resources on the Moon?

With all these different players headed to the lunar surface, is there enough Moon for everyone? In 2020, NASA announced that it had found the best evidence yet that water trapped in icy pockets were far more spread out across the lunar surface than previously believed.

“Water is a critical ingredient because you can take that frozen water and turn it into oxygen to breathe and separate the hydrogen to make fuel for rocket fuel,” Impey said. “And so you don’t have to drag all that stuff from Earth, which is very expensive.”

The renewed interest in the Moon is mainly focused on the lunar south pole, where these reservoirs of icy water are believed to exist. NASA wants to land its Artemis 3 astronauts on the south pole, and China is looking towards that same region for its own crewed lunar landings.

NASA Administrator Bill Nelson frequently mentions China’s efforts to get to the Moon, fearing that it might try to take over precious resources. “You see the actions of the Chinese government on Earth. They go out and claim some international islands in the South China Sea and then they claim them as theirs and build military runways on them,” Nelson said during a press conference in August. “So naturally, I don’t want China to get to the south pole first with humans and then say, ‘this is ours, stay out.’”

Whether it be for Artemis or the management of the International Space Station (ISS), NASA has partnered with the European Space Agency, Canada, Japan, and others. “So the only country that the U.S. is not working with right now in space is China,” Burns said. “That has to do with the power politics of today, but does that mean there’s a race between the U.S. and China in space? I would say no, because I don’t believe either country really looks at space as being a race.”

“Both countries are proceeding at their own pace while not necessarily being driven by the other,” he added.

As of today, however, there are no laws governing both countries in space the same way that they are governed on Earth. “The backdrop for all of this is that it’s a lawless Wild West because there’s no space law that applies to them,” Impey said.

The Moon is about a quarter the size of Earth. It’s still a vast physical object, but the fight over resources on Earth could extend to the planet’s natural satellite, where the same rules don’t apply. “There’s no ownership for resources,” Impey added. “So it’s up for grabs. I mean, the whole thing.”