When It Comes to Exploring Space, We’re Still Stuck in the Stone Ages

We’re rapidly approaching the quarter mark of the 21st century, but instead of being at the brink of a radical transformative stage, such as the futuristic vision akin to Arthur C. Clarke’s Star Child from 2001: A Space Odyssey, we’re still throwing proverbial bones into the sky.

Such is the feeling I get in the wake of three recent Moon missions, in which two spacecraft, Japan’s SLIM and Intuitive Machines’ Odysseus, survived despite falling awkwardly onto the lunar surface, while a third, Astrobotic’s Peregrine, failed to reach the Moon entirely.

These episodes are making me feel grumbly and increasingly impatient about our space ambitions. How is it that we’re still struggling with such things? Like, shouldn’t this be a piece of cake by now?

These missions were all successful in the sense that they moved the needle, but humanity’s collective space needle needs to move a whole lot more in the coming years and decades if we’re truly going to match the expectations set out by futurists, sci-fi authors, and, to be fair, much of the public in general, like establishing colonies on the Moon and Mars, exploring the hidden oceans of distant moons, or embarking on interstellar voyages. These latest Moon missions are an important reality check, reminding us of where we stand in the cosmological scheme of things.

Despite our remarkable achievements spanning almost seven decades in space exploration, we’re still very much infants when it comes to venturing beyond Earth’s immediate environment. Space, as a meaningful place for humans to explore, work, and live, remains woefully out of reach.

The space delusion

The recent forays to the Moon emphasize once again that space is hard, but beyond this overworked, tired cliche, these missions underscore how rudimentary our capabilities still are in terms of living and working in space. Fifty years after Apollo, we’re still struggling to land spacecraft on the Moon, let alone live in orbital habitats, occupy Mars, or embark on crewed missions to the outer solar system.

Apollo, and the Space Shuttle to a certain degree, left us with the false impression that space is now our regular stomping ground, but nothing could be further from the truth. Space, as a consequential working environment for humans, remains an illusion. We are stuck on this planet for the foreseeable future, regardless of what billionaire CEOs and their devotees might say. Terrestrial confinement continues to define the human condition, and in this aspect, we’re far closer to the Napoleonic era than we are to the latest season of For All Mankind.

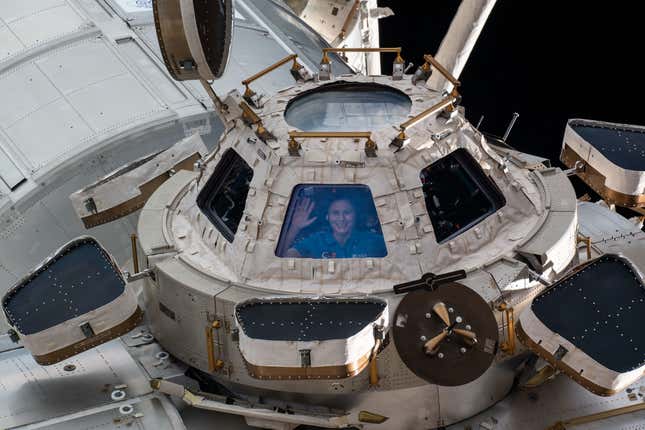

Which does not discount our litany of impressive space-based accomplishments. We’ve famously walked on the Moon, built an international space station in low Earth orbit, placed robots on Mars, and sent multiple probes on journeys to the outer realms of the solar system, among many other technological feats. Stepping back, however, our abilities seem rather limited.

Virtually no one goes to space

Fewer than 650 humans have visited outer space. That’s a sobering reminder that the final frontier remains an exclusive and elusive place for members of our species. For the privileged few who have had the opportunity to journey into space, missions typically range from a couple of weeks to six months, with rare instances lasting a year or more. Simply put, humans don’t visit space for the most part, and those who do don’t stay for very long.

And as we’re learning, the microgravity environment wreaks havoc on the human body, inflicting such problems as weakened bones, muscle atrophy, vision impairment, and altered cardiovascular function. We can develop as many advanced technologies as we like for traveling to and working in space, but until we discover methods to either prevent and treat these health conditions or adapt the human body to the space environment, we remain fundamentally bound to life at the bottom of Earth’s gravity well.

For those dreaming of space tourism, the reality is far from ideal due to the limited state of the technology and the absurd costs. Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin currently offer experiences that barely qualify as space travel, with brief flights that flirt with the Kármán Line and last only a few minutes. Such fleeting journeys are a stark contrast to the envisioned future of the space tourism industry, which includes luxurious hotels orbiting Earth and scenic tours around Saturn’s rings.

The new space race?

As further evidence of our current limitations, a single company—SpaceX—dominates the market for rocket launches. That’s intolerable, and a hurdle that needs to be overcome.

Rocket reusability remains the key innovation driving this near-monopoly, prompting the rest of the industry to scramble to develop comparable solutions, none of which yet exist. Until SpaceX’s competitors catch up, cost will remain a critical barrier to reaching space, in addition to rocket scarcity. Just ask Europe. But the fact that we’re still talking about this—how one company can still dominate this realm—just reinforces that the space launch industry remains in a primitive state.

That said, the industry has entered into an important new phase, with spaceflight evolving from a domain exclusively managed by governments to one increasingly dominated by private sector initiatives. The race to monetize space is on, from lunar delivery services and commercial space stations through to the extraction of valuable resources from asteroids and the Moon. Some of these NewSpace ventures are being headed by billionaires, while others are startups dependent on thin margins and speculative markets. Richard Branson’s Virgin Orbit declared bankruptcy last year, while space tug company Momentus and rocket company Astra teeter on the edge, as just a few examples of the current precariousness of the industry.

The financial hurdles, though significant, pale in comparison to the immense technological challenges these companies face. I am confident that commercial space stations and trips around the Moon will eventually become a reality, but not imminently, and it’s unlikely to be an experience accessible to the general public anytime soon.

Astronomically limited budgets

I’m a big proponent of NASA’s Artemis program. It may seem as though NASA is having to reinvent the wheel when it comes to returning boots to the Moon, but these missions, when compared to Apollo, are a horse of a different color, both in terms of budget and the space agency’s ultimate goal: making it possible to safely and sustainably work in the lunar environment. Whereas Apollo was about getting astronauts to the Moon and back as quickly as possible, Artemis is dedicated to the long game and to developing the tools and skills for eventually sending astronauts to Mars.

Related post: Did NASA Forget How to Put People on the Moon?

Big things will come of this, of that I’m fully confident. As for the timelines involved, I’m considerably less sanguine. Achieving seamless travel between the Earth and Moon, and building the required infrastructure, requires advanced technologies that are much farther than they appear. Moreover, a critical hurdle lies in the lack of enthusiasm for spending within the U.S. Congress, which holds the key to funding such endeavors.

Without the requisite funding, progress in these areas will continue to advance at a snail’s pace. NASA is increasingly turning to the private sector as a means to cut costs and foster innovation—a sensible strategy, no doubt—but the resulting shoestring budgets for the companies involved results in, well, those imperfect Moon missions we saw earlier this year. Keep in mind that NASA, back in the early 1960s and with nearly unlimited access to funds, regularly placed its Surveyor landers on the lunar surface in preparation for the Apollo missions.

Indeed, money, and the incredible resources it brings to bear, can result in some extraordinary things, as Apollo proved, but the ideological landscape has changed radically in the past 50 years. Washington no longer views space exploration as a matter of existential importance, as it most certainly did during the Cold War, and federal funding has shriveled as a result. Apollo consumed a substantial portion of resources, with NASA receiving 5% of the federal budget. In contrast, today its allocation is less than 0.4%, as Jack Burns, a professor in the physics department at the University of Colorado-Boulder, told Gizmodo last year. Congress is no longer willing to throw endless buckets of money at NASA, with some of today’s flagship missions, such as the Mars Sample Return mission, now at risk.

NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) rocket, which debuted in 2022, isn’t helping the budgetary situation. The overall cost of a single Artemis launch has been pegged at an alarming $4.2 billion, which NASA itself has admitted is an “unaffordable” expense. The fully expendable megarocket is already an anachronism.

The space agency is now burdened by an outdated and cost-inefficient rocket system, a direct consequence of prior decisions that failed to recognize pending technological advancements and financial practicalities. Cash-strapped NASA is stuck with SLS, and as a result, it’ll have to operate at a plodding pace for the foreseeable future. Speaking of sluggish progress and outdated technologies, astronauts aboard the ISS are still using spacesuits built more than four decades ago.

Cold War rival Russia is falling woefully behind, too. Russian president Vladimir Putin shows more interest in extending his country’s borders than in expanding Russia’s reach into the stellar void. Russia also seems focused on building tools to disrupt the delicate house of cards that the U.S. and its allies have set up in space, with recent warnings of nukes in orbit. Indeed, it’s far easier to destroy than it is to build, so for a nation that’s lagging behind, this strategy makes pure Machiavellian sense.

Meanwhile, China and India are all systems go, developing their respective space programs at a breakneck pace. Perhaps the threat of Chinese astronauts on the Moon will entice Congress when it comes to loosening the purse strings, but only time will tell.

Losing space entirely

Another key issue to consider is space traffic management and the mounting threat of orbital debris. We have all of these incredibly ambitious plans for space, yet we currently lack the capacity to keep it clean up there. Defunct satellites, abandoned rocket parts, and dangerous flecks of debris are accumulating faster in orbit than they are disappearing, leading to concerns of the Kessler Syndrome—a scenario in which the density of objects in low Earth orbit is high enough to cause a cascade of collisions, resulting in an exponentially increasing amount of space debris that traps us on the surface.

We risk transforming low Earth orbit into a perilously hazardous zone, rendering it unusable for an extended period and hindering future space endeavors. Seems unfathomable, but there’s a danger of regressing to a pre-spaceflight civilization. We can avoid this, of course, by funding the development of advanced space debris removal technologies and implementing stricter regulations on satellite launches and end-of-life disposal practices.

Galactic patience required

All of this needs to be evaluated against potentially more pressing challenges on Earth, such as climate change, pandemics, global poverty, and dangers posed by advanced technology like artificial intelligence and nanotechnology. A strong case can be made that preventing existential risks—that is, the prevention of human extinction—is a considerably higher priority than scooting around the lunar surface on Moon buggies.

I won’t belabor the commonly expressed belief that we must gain the ability to live off-planet as a means to save ourselves from ourselves; it’s evident that developing the capacity to live beyond Earth is a worthwhile endeavor and an excellent long-term goal. Ultimately, however, we need to strike a balance between our ambition to establish life beyond Earth and our commitment to addressing the numerous challenges we face here on our home planet.

This approach is essential if we wish to prosper as a species and flourish in the future, yet it comes with its compromises, including the slowed progression of our spacefaring capabilities. But that’s actually okay. We’re having to learn and accept that space is a plodding affair, with other priorities vying for attention. I’ll be sure to remind myself of this the next time a lunar lander literally bites the lunar dust.

For more spaceflight in your life, follow us on X and bookmark Gizmodo’s dedicated Spaceflight page.