Queer Pirate Fantasy Running Close to the Wind Excerpt

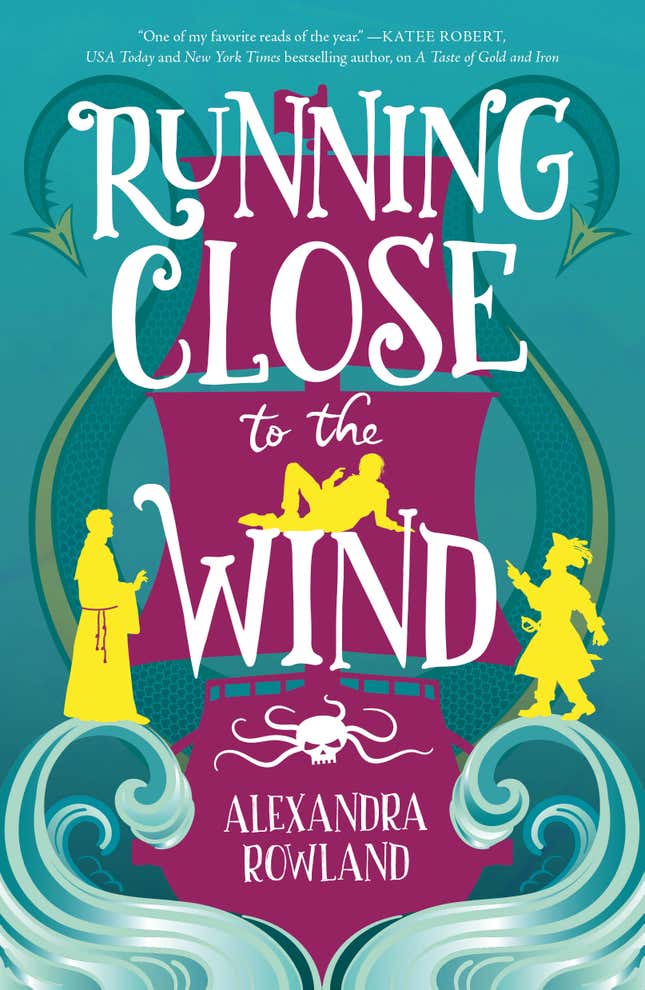

Listen, anything billed as “for fans of Our Flag Means Death” is going to snag our attention—but when it’s describing the latest from A Taste of Iron and Gold author Alexandra Rowland, our interest becomes even more intense. io9 has the cover and an exclusive excerpt to share from Running Close to the Wind, the author’s 2024 queer pirate fantasy adventure.

Here’s a description of Running Close to the Wind:

Avra Helvaçi, former field agent of the Araşti Ministry of Intelligence, has accidentally stolen the single most expensive secret in the world—and the only place to flee with a secret that big is the open sea.

To find a buyer with deep enough pockets, Avra must ask for help from his on-again, off-again ex, the pirate Captain Teveri az-Ḥaffār. They are far from happy to see him, but together, they hatch a plan: take the information to the isolated pirate republic of the Isles of Lost Souls, fence it, profit. The only things in their way? A calculating new Araşti ambassador to the Isles of Lost Souls who’s got his eyes on Avra’s every move; Brother Julian, a beautiful, mysterious new member of the crew with secrets of his own and a frankly inconvenient vow of celibacy; the fact that they’re sailing straight into sea serpent breeding season and almost certain doom.

But if they can find a way to survive and sell the secret on the black market, they’ll all be as wealthy as kings—and, more important, they’ll be legends.

Check out the full cover (art and design by Christine Foltzer), and enjoy the excerpt below! Running Close to the Wind releases June 11, 2024, and you can pre-order a copy here.

As soon as he saw that ship come over the horizon, Avra Helvaçi said, “Eeee,” scurried to his tiny cabin so he would be safely out from underfoot, shut the door, sat on the bunk with his little rucksack clasped in his lap, and began to mentally compose and rehearse the apology he would imminently need to present, if only to keep himself from being shoved overboard and left for dead. Again.

After a few moments of silence, he fumbled in his rucksack and pulled a single card from his deck of Heralds.

The Broken Quill: Damaged lines of communication; frustration will ruin delicate things.

Bit on the nose, really, and nothing he didn’t already know.

He tucked it away, clasped his hands tight between his knees so he wouldn’t vibrate out of his skin, and went back to visualizing minute variations of his apology. Teveri deserved only the best, of course.

Once The Running Sun overtook them, the rest was a quick affair. Avra prided himself on a single scanty fistful of common sense, and he was rather pleased to have correctly assessed the captain of this vessel as a man too sensible to put up much of a fight when boarded by pirates.

As the clamor and fuss on deck came to a resolution, Avra bounced his knee and hummed a nervous little tune to himself, one of his own compositions, and continued reflecting upon his predicament. Did he recollect what Teveri had been mad about last time? No. Tev was always mad about something. Who could possibly keep track of Avra’s various wrongs?

He would apologize nicely for as many things as he could think of, then, and that would smooth any still-ruffled feathers. Definitely.

And if not, well . . . It was far preferable to die at Teveri az-Ḥaffār’s hand than . . . the current most probable alternative. He tried not to think about that.

The noise quieted marginally, which meant that Captain Veris’s crew had surrendered and that The Running Sun’s crew would now take inventory. They’d search the hold and each cabin, and eventually . . .

Someone—a big, brawny, sweaty someone with the sleeves ripped off his shirt and tattoos down his arms—shouldered Avra’s door open.

“Ah! Oskar!” Avra said, slightly manic. He pasted a delighted smile across his face. “It’s been too long!”

Oskar, Teveri’s second-mate, stared at him. “Aw, fuck,” he groaned. “No, no, no.”

Avra pouted. “Are you not pleased to see me? I missed you terribly.”

“No no no no,” Oskar said, backing out of the room. “No, no, no.”

“What’s the matter?” said a familiar voice from behind Oskar.

“No,” Oskar moaned again. “Fuck.”

“You seem a bit concerned,” Avra said. “Not to worry! I have a plan.”

“Nooo,” said Oskar.

“I,” Avra announced grandly, “am going to say sorry! Then all will be well, and Tev will forgive me.”

Another face poked around the doorway—a woman toward the end of middle age, with steel-grey hair cropped close to her scalp and dark skin weathered by sun and salt and wind.

“Markefa!” Avra beamed. The mild frown on Markefa’s face melted into poleaxed astonishment. “What a nice surprise! You were talking so much about retirement last time, I was all prepared to find you’d gone ashore for good. How’s the leg? All healed up? How’s the family?”

“Ah, fuck,” said Markefa.

“You know, I really think you’re both overreacting just a little teensy bit, maybe,” said Avra. “Listen, though, I can’t decide—do you think Tev would like it if you delivered me to them hogtied?”

***

“Hello, incandescent one,” Avra said adoringly, lying hogtied at Teveri’s feet on the deck of their ship.

The Running Sun was a carrack of three masts, somewhere between meh and decent in quality: On the upside, she had been designed by the Shipbuilder’s Guild of Araşt to its famously exacting standards, including quality-control inspection, certification, and her inaugural hull-painting, though that had long since worn off. On the downside, due to the circumstances around how Teveri az-Ḥaffār had become captain, all the other pirates sneered and said mean things about how the ship was cursed or haunted or what-have-you. This made the crew a bit collectively defensive, in Avra’s opinion, and it was one of the many, many things Teveri was mad about.

Once, Avra had barely mentioned the rumors and stories of how Teveri had acquired the ship. Teveri had immediately dragged him by his hair out of both bed and the afterglow and had thrown him bodily out of the cabin, followed by his trousers and boots. He could not prove that they’d aimed for his head, but the suspicion was certainly there.

“Before we say anything else,” he began in his politest tones, “I want to express my deepest and sincerest apologies. I see now that I have behaved in an ungentlemanly manner. I have been an outright blackguard. A cur. A cad. Not to mention disrespectful, impolite, and indeed both churlish and childish. Moreover, I have been that greatest of reprobates—a flibbertigibbet. Not a moment has passed that I have not regretted every aspect of our last parting. I have torn my hair over it. I have lost sleep over it. I ache with remorse. On my honor, such as it is, I shall be a good and sweet little Avra henceforth, particularly if you could maybe see your way to not putting me in a rowboat in the middle of the ocean and sailing off without even a wave of a handkerchief in farewell.” Again. “I must say it’s good to see you, though. You look ravishing in those boots. Are they new?”

Teveri kicked him sharply in the stomach. Frankly, it was an honor. “How are you alive?”

“Got lucky,” he wheezed. “Tev, light of my life—”

Another sharp kick. It was somewhat less of an honor (though the boots were still ravishing).

“I won’t do it again!” Avra squeaked. “I’m sorry! You’re completely right to still be angry at me. I too would still be angry at me! I gave you a tip-off for what was probably a wild-goose chase, and then when you tracked me down to very correctly take vengeance upon me for wasting your time, I didn’t even—”

“You think I bothered following your stupid little hunch, Avra?” Teveri snarled. “Stupid, incoherent, written on the back of a napkin—”

Avra wriggled valiantly and managed to tip himself upright with a little “hrgkgh” of effort, which he hoped came across as endearing, and pouted up at them. “You didn’t go on my wild-goose chase? I really don’t know what else you have to be mad at me about, then. Maybe you should apologize too—if I didn’t do anything, then your response was maybe a little disproportionate—”

Teveri’s black right eye flashed with fury, even brighter than the gold orb that replaced the left. “Your motherfucking song.”

“The s— Ohhh, the song.” Avra arranged his face into the most plaintive expression in his inventory. “You didn’t like the song? I thought it was a good song. Complimentary, even.” Some of his best work, really. He’d rhymed “strap-on” with “denouement” and had thought himself very clever. He’d added seventeen more verses to it in the time that it had taken to get a lucky rescue from that rowboat Tev had marooned him in.

The scarred side of the captain’s mouth twisted up, baring their teeth. Gods, Tev was magnificent.

“Ah,” he said. “Aha. Well . . .” Shit, he hadn’t prepared for this one. “No accounting for taste,” he said brightly. “Wait, fuck, no, that’s wrong. Didn’t mean that—” He flung himself aside with a high “reeeee!” of alarm, and Teveri’s next kick just missed him. “It was supposed to be a nice song! I told everyone in that bar that your ship definitely isn’t haunted or anything, and that you’re great at both pirating and fucking! And that the only marginally spooky thing about you, since your ship is incredibly non-haunted, is that you’ve got a box full of terrifying spooky dildos!” He gave Teveri a limpid glance up through his eyelashes. “I thought you’d like it. I thought it would help your reputation. Should I have not mentioned your box of spooky dildos? Won’t do it again. Honest, Tev.”

“The sea will boil before a single honest word falls from your tongue,” Teveri said, aiming another kick at him, which he rolled to dodge with another “reee!!!” which he thought gave him a rather pathetic air. Tev wouldn’t kick a man who made undignified noises when threatened, would they? It would be beneath them.

Very few things were beneath Captain Teveri az-Ḥaffār, as it turned out. The next kick landed right on Avra’s bum.

He groaned in defeat (and pain), rolled onto his back, and attempted to maximize the limpidness of his pleading gaze. “Tev—”

“Call me that again, I fucking dare you.”

“Captain az-Ḥaffār,” he amended. “Let’s talk about this. I’m sorry about the song. Though you should know that lots of people told me it was surprisingly sexy! Well, technically they said ‘unexpectedly sexual,’ but the tone was ambiguous. Never mind that! If you don’t like it, then every word of it is as ashes in my mouth! I can write you a new song. A new, different, better song. I’ve recently quit my dayjob to pursue my poetry, you see, so I have quite a lot of free time!”

Teveri put their hands on their hips and their head a bit on one side. “What do we have that’s sticky? Just pitch for the hull, no?”

“What are you wanting sticky shit for, Tev?” Avra asked suspiciously.

“Tarring-and-feathering you.”

“But I don’t want to be tarred-and-feathered.”

“Just pitch, Captain. We’ve got some extra from their stores,” Markefa called from the rail where the crew was hauling the last of the contents of the other ship’s hold into theirs on platforms hung from ropes and pulleys at the ends of the yardarms. The other crew had been released and was already scurrying to get their sails in order and run away before The Running Sun decided to take anything else from them. “Do you want to use some of this straw instead of tearing up one of those nice pillows we took from the captain’s cabin?”

Teveri seethed. “We might as well.” To no one in particular, they snapped, “Why do these people have a hold full of fucking straw and nothing else?”

“Fancy hats,” said Avra promptly.

Teveri looked down at him with an expression of exasperation so profound it was nearly sorrow. “What?”

“It’s for fancy hats,” he chirped. “I asked too. Fashion for fancy hats in Map Sut this year, the captain told me. But to make them, they need this particular kind of braided straw, and the place that does the braiding isn’t the same as the place where that specific variety of rye grows, so they have to import it. Hold full of cheap straw, take it to whatsits-place and pay to get it all braided, haul the spools of braid off to Map Sut, sell them for a fat profit. That’s called a good return on investment, Tev. It is a solemn thing of great reverence where I come from, you know. Please respect my culture.” Teveri pinched the bridge of their nose again and breathed several times.

“Don’t grind your teeth,” Avra reminded them helpfully. “Remember what that dentist said? He was far more spooky than you, by the way. Remember he said you had to stop grinding or you’d crack one. Anyway, it’s quite nice straw. Nicest straw I’ve ever seen, anyway, not that I know anything about . . . straw.” He paused. “Maybe not what you were hoping to score, though. You seem grouchy about it. Are you having money problems again?” Teveri feinted another kick at him—Avra didn’t see why that deserved a kick, but he obligingly made another pathetic, undignified sound.

The Running Sun was nearly always having money problems. Ships took a lot of upkeep, and crews needed a lot of food, and then there were things like the pension fund for any of the crew who got injured or killed . . . Money was never really good on a pirate ship, and The Running Sun had never managed a really big score—which only played into the rumors that the ship was cursed.

As soon as Avra moseyed past that thought, his brain pounced, supplying some lightning-fast calculations: It was awfully late in the season for The Running Sun to be out on the water—there was only a fortnight or so until the sea serpents rose from the abyssal depths for their breeding season, making the open ocean too dangerous for anyone sane to risk sailing into blue water for at least six weeks. (That is, unless they were an Araşti crew on an Araşti ship . . . and in possession of what was in the little rucksack Avra had been clutching for the past two days.) The ship they’d just captured was only a few days out from the port they planned to shelter in, but The Running Sun should have been much farther south—either already anchored safe in the Isles of Lost Souls or at least making her way there before the water frothed up into terrifying swarms of teeth and . . . well, mostly teeth. So many teeth. Teeth and horny rage.

There was no chance that the crew would be planning to anchor somewhere else—other captains might have contacts in secure ports that would allow them to shelter there if need be, but not Teveri az-Ḥaffār . . . And of all the pirates Avra was acquainted with, there was neither captain nor crew who would voluntarily spend the season of serpents away from the Isles of Lost Souls. It was a crucial and unmissable opportunity to be seen by the other crews, to brag and boast and bolster one’s reputation in pirate society (such as it was), to make deals and alliances, to get even for past slights, to get yourself hired by a new ship if the old one no longer suited . . . And there was the fun and spectacle of all the festivities, of course. As far as Avra was concerned, the only people who would voluntarily miss the cake competition were the ones who didn’t know about it.

In conclusion: The Running Sun must have money problems, and the crew, facing the prospect of a six-week enforced holiday they were too poor to enjoy, must have voted to try for one last score to fill their coffers before they flew back to the Isles, probably reaching port just as the sea was due to become . . . unpleasantly teethy.

Avra did not like the idea of being tarred-and-feathered—or tarred-and-strawed, for that matter—and summarily marooned again, especially when most of the other boats that could have coincidentally rescued him were already finding safe harbor and settling in for the serpent season.

He glanced down at his little rucksack, which held the entire reason that he had been able to quit his dayjob as a field agent of the Araşti Ministry of Intelligence in order to pursue his poetry career. Offering to share it would almost certainly absolve him of being tarred-and-feathered and left for dead, because selling the contents would solve The Running Sun’s money problems a hundred times over. A thousand. At that point, they might as well all retire and buy charming villas somewhere on the coast of Pezia.

He hadn’t entirely decided whether he was going to sell it—it would be an unconscionable amount of money. The idea of sharing that amount of money with the crew was a much easier decision to make. He glanced up at the rigging, at the mainsail . . .

The literally priceless mainsail. It technically belonged to him. Technically. He’d won it off another captain in a card game, years and years ago. He probably could have quit his dayjob right then, but selling it hadn’t even occurred to him. He’d given it to Tev without a second thought, because . . . Well, because what was the point of having money if you didn’t have friends? There was a difference between Tev being mad at him for something and Tev literally never forgiving him, after all, and selling that mainsail just to line his own pockets would have done it. It would have been disrespectful, bordering on sacrilegious, and there were things that even Avra had to take seriously. That mainsail, for one. Also the cake competition. And . . . what would happen if anyone from Araşt found out what Avra had taken.

He looked down at his little rucksack again. Sharing the wealth also meant sharing the danger. He’d been leaning away from the idea of selling it because thinking about the potential consequences made him want to throw up, and because he did pride himself on one single scanty fistful of common sense, which had suggested to him two days ago that the smart plan was to hightail it out of Araşt at top speed, cover his tracks by being captured by pirates, fake his own death, change his name, move to another country where no one knew him, find a cheap boardinghouse that would rent him a grubby room with a loose floorboard he could stuff his spoils under, live out the rest of his days eking out a living with his poetry and looking over his shoulder for assassins from the Ministry of Intelligence, and never tell anyone about what he’d done.

Well, that was the second smartest plan. The first was to immediately burn all the papers and keep his mouth shut, but every time he’d considered that, he’d thought, But what if I need it one day, what if I need it to bribe someone not to kill me?

He hadn’t expected that one day to happen this soon.

Two of the crew rolled a barrel of tar over to Tev, and another person—a newcomer, as Avra didn’t recognize them—guided the loading platform onto the deck and swung off one of the bales of straw. Avra wriggled fiercely, but Oskar and Markefa’s knots were, of course, impeccable.

***

Avra couldn’t quite bear to play his trump card yet. Never mind the money or the potential consequences—the simple concept of other people knowing about it was still too huge and nauseating to contemplate. He compromised with himself and decided to try one more round of cajoling. “Listen, let’s not do this!” he said loudly. “You’ll probably get tar all over the deck, and I will be a truly pathetic sight during the whole process—you’ll all be very embarrassed to know me!”

Teveri drew one of their knives and slashed the strings binding the bale together. Fragments of straw fell free, standing out against the worn, greyish deck in shards of a bright silver-gold that shone prettily in the sun and must have made for a very fine hat.

“You know, on balance, I don’t think we should give him one of our rowboats this time,” Teveri announced, viciously demolishing the tight bale into a loose, shining pile. “I think we should just toss him in.”

“Reeee,” Avra said piteously, but it made no difference. “But what if I suddenly prove terribly useful?”

“Oh, trust me, this whole situation is going to be very useful to me later tonight when I’m getting myself off to the thought of finally being rid of you. Markefa, open up that barrel.”

“Aye, Captain,” Markefa said complacently, and began to work it open with her big knife.

The black, hot scent of tar trickled into Avra’s nose. “Tev, Tev, Tev. Teveri. Captain az-Ḥaffār. Do not cover me in tar, please, we should probably talk first, I have a really neat thing to tell you about, I swear on my own dick that I’ve got something unbelievably nifty—”

Markefa paused, the lid half-pried off, and raised an eyebrow at the captain.

“What?” Teveri snapped.

“Swears on his own dick, Captain,” she said, a little reproachful. “Oughta hear a man out when he swears on his own dick, no?”

Teveri glared. They were fairly-well covered in straw—there were fragments of it clinging to their front and the stained threadbare sleeves of their shirt, pieces of it scattered through their hair, shards of it stuck to their golden-brown skin.

Ah, gods above and below, but they were splendid, even with their dark hair all ratty and mussed from battle, most of it stringy and half-damp with sweat, the rest windblown, gritty, and dull from the build-up of salt spray.

So actually kind of disgusting, really, but . . . ah, just splendid, even so.

Teveri turned their glare onto him and snarled, “You have sixty seconds. Only because Markefa asked. Say thank you to Markefa.”

“Thank you, Markefa,” Avra squeaked.

Teveri crossed their arms and stared down at him, impassive beyond a crisp air of expectation.

After a few moments, Avra said, “Oh, shit, did my time already start? You didn’t say my time already started!”

“Oh boy,” said Markefa.

“So it’s kind of a long story,” Avra babbled as fast as he could, “and really it’d land better if you were to hear the whole thing, because you’d probably think it was really funny—but, ah, right, to summarize it in an efficient, sixty-second sort of way—less than sixty seconds, really, because you didn’t tell me my time started—anyway, the short version! So you remember ages ago when we went to Quassa sai Bendra and that thing happened, and everybody got huffy and called me a cheater ’cause I kept winning at card games, and then those other things happened and everybody got superstitious and called me a witch ’cause lucky shit kept happening to me, and I kept saying, ‘What, that’s stupid, I’m not a witch, my luck is normal’? Well, after the friendly misunderstanding wherein you marooned me at sea because of that very bad and inappropriate song I wrote—after that I sort of, well, ahaha, I sort of felt as though getting rescued from certain death by a ship conveniently bound for Araşt was the sort of suspiciously good fortune that was worth thinking about, and I said to myself, ‘What if I tried poking my weirdly good luck a little bit, just to see what happens, maybe I’ll just do a couple fun little experiments like a natural philosopher—’”

“Time’s up,” Teveri said flatly, and moved toward the barrel of pitch.

“I copied a bunch of secret papers from the headquarters of the Araşti Shipbuilder’s Guild in Kasaba City and I have them with me right now!” Avra shrieked.

Teveri paused.

The entire deck went dead silent but for the sound of the water against the hull and the creak of the rigging in the wind.

“Good papers! Important papers! They were locked in a safe!” Avra panted, wriggling energetically away from the barrel of tar. “There was an incident where somebody tried to break into the Guild—let’s not get into it, actually, not important—I just wanted to see how far my luck went! Answer: Pretty fucking far, actually! And at this juncture, I would like to tactfully point out that if I were to be shown some affection and generosity—for example, by not being dumped overboard—then I would absolutely feel inclined to reciprocate that affection and generosity by . . . by sharing? Sharing what I have? Equal shares! And maybe we can talk it through as a crew and someone more sensible than me can figure out how we can all be rich and, crucially, not dead?”

The entire deck was still utterly still and silent—he had everyone’s attention. Maybe this was not sufficient to atone for his crimes. Maybe it was in fact all the more reason to dump him overboard. he flicked his eyes up, deliberate, to The Running Sun’s glittering cloth-of-silver mainsail.

That sail was a large part of why the crew had put up with him for so many years, and why he was pretty fucking confident they, with this little reminder, would intervene on his behalf if Tev kept refusing to be reasonable.

It had been his eerie luck working during that card game too, hadn’t it? No one just swanned into the Isles of Lost Souls, anchored in Scuttle Cove, went for a drink at the Crowned Skull, challenged Captain Luchenko of the Merry Maid to a game of dice, won without losing even a single copper piece of any nation’s currency, and walked away with one of the greatest prizes ever won in that dingy bar.

No one did that.

But Avra had done it.

Avra looked up at the silver sail, by far the biggest surviving relic of the legendary Nightingale, and listened to the crew fidget and shift on their feet as the reminder sank in. He added, just a little extra nudge, “I’m ever so inclined to be generous to friends—family—who have been so generous to me. Who’s to say how much these papers could sell for? Lots of stuff you can buy with an unimaginable mountain of money. Probably still have some left over. You could spread it out on a bed and roll around naked on it. Could do all sorts of things with that much money.” He paused again. “Whats-his-name, Captain Ueleari—doesn’t he have a standing offer to sell the Nightingale relics he’s got? What was it—the mizzen royal and the flag for the bargain price of one million Araşti altınlar? Imagine. Imagine having the mizzen royal, the mainsail, and the flag of the Nightingale, and still having enough money left over that you’re sleeping and swiving on gold and picking silver and copper out of your asscrack.”

The crew stirred again. Avra glanced at Tev, who was grinding their teeth with no regard for the advice of spooky dentists, and then at Markefa, who was giving the captain significant looks.

“It’d do a great deal to ease the sting of this bullshit,” Markefa murmured with an almost invisible nod to the straw. “Go a long way to making everybody feel better about the two last month as well.”

“What were the two last month?” Avra asked.

“Boxes of fucking rank swamp muck from Kaskinen, bound for Heyrland. Didn’t see the point of taking anything from them but their food and supplies.”

“Wow,” said Avra. “Bad luck. So fancy straw’s kind of a step up at the moment, huh? Well, fancy straw and your favorite poet in the whole wide world and a bunch of papers constituting what is very possibly the most expensive secret in recorded history. Well, half of it,” he lied quickly as the thought occurred to him that “your favorite poet in the whole wide world” was the sort of cargo which could and arguably should get thrown overboard. “The other half is in my head. So you’ve got to keep me alive if you want it to be worth anything at all.” A classic gambit, but it was a classic for a reason.

Tev grimaced. “Put the tar away, and throw this motherfucker in the rope locker. Don’t untie him. I haven’t fucking decided what I want to do with him. And don’t,” they added in a snarl, loud enough for the whole crew to hear, “do not speak to me about him, do not mention him to me, and I fucking dare you to hum even one bar of that song.” They glared fiercely—fierce enough that several of the crew in the immediate vicinity muttered about not being that horny for a fight.

“The rope locker!” Avra said meanwhile. “My old friend the rope locker! Cozy! Oskar, carry me gently, alright? You were so rough a minute ago, and I bruise so easily. I’m delicate, Oskar, you know I’m delicate—”

Excerpt from Alexandra Rowland’s Running Close to the Wind reprinted by permission of Tor.

Running Close to the Wind by Alexandra Rowland will be out June 11, 2024; pre-order here.

Want more io9 news? Check out when to expect the latest Marvel, Star Wars, and Star Trek releases, what’s next for the DC Universe on film and TV, and everything you need to know about the future of Doctor Who.

اكتشاف المزيد من موقع دبليو 6 دبليو

اشترك للحصول على أحدث التدوينات المرسلة إلى بريدك الإلكتروني.