Read a Spooky Story From New Indigenous Dark Fiction Anthology

Edited by Shane Hawk and Theodore C. Van Alst Jr., Never Whistle at Night: An Indigenous Dark Fiction Anthology features an introduction by acclaimed horror author Stephen Graham Jones and unsettling tales by a wide range of Indigenous authors. io9 is thrilled to share one of the entries, “Night in the Chrysalis” by Tiffany Morris, ahead of the collection’s September 19 release.

Here’s a bit more about the anthology:

Many Indigenous people believe that one should never whistle at night. This belief takes many forms: for instance, Native Hawaiians believe it summons the Hukai’po, the spirits of ancient warriors, and Native Mexicans say it calls Lechuza, a witch that can transform into an owl. But what all these legends hold in common is the certainty that whistling at night can cause evil spirits to appear—and even follow you home.

These wholly original and shiver-inducing tales introduce readers to ghosts, curses, hauntings, monstrous creatures, complex family legacies, desperate deeds, and chilling acts of revenge. Introduced and contextualized by bestselling author Stephen Graham Jones, these stories are a celebration of Indigenous peoples’ survival and imagination, and a glorious reveling in all the things an ill-advised whistle might summon.

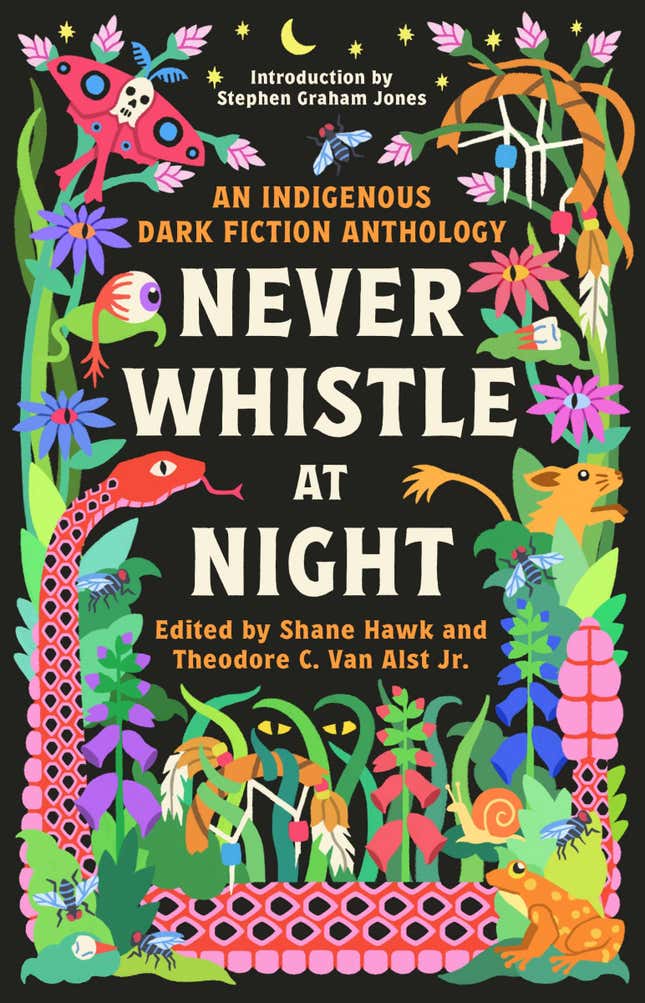

Here’s the full cover, followed by “Night in the Chrysalis” by Tiffany Morris.

Night in the Chrysalis

Tiffany Morris

A woman’s voice, soft with lullaby, sang its wind-chime strangeness into the dark.

Cece woke with a start.

“Kwe’?” she asked. Wide-awake in the dark, no light came through the bedroom window. “Hello?”

The woman’s voice was coming from another room. Cece fumbled for her phone and saw the time: 11:45 p.m. Still early. She wished that daylight was shuffling closer.

She turned to the flashlight on her phone and found her battery-powered lantern. She clicked it on, its yellow brightness a little stronger than her phone’s dim light, and stepped out into the dark hall.

“Is someone there? I already called the cops,” she lied. She wandered, shaking, to the room across the hall. The cold brass knob turned with no effort. A rustling sound scurried over the floor. She shone her lantern there.

Eyes were watching her in the dark but she could not see them. The streetlight moon outside sent unreal shadows into the empty room. The light itself searched the darkness for her, living prey watched by walls and windows—

Her flashlight landed on a small object. She squinted and moved closer: sticks tied together with jute string, a crude bundle in the rough shape of a person.

She screamed and dropped it. She ran down the spine of the house, her body a shiver traveling over the staircase.

Cece messaged her aunt. Did you smudge this place yet?

Her aunt saw the message. The typing ellipses popped up. They disappeared. They popped up again. Cece waited, stomach in knots, for her aunt’s response. They disappeared.

Nothing.

Fuck, she thought. She didn’t have anything to smudge the place—or herself. The power wasn’t on yet, either. It would just be her, her flashlights, and what was left of her phone and laptop batteries.

Cece’s life had become a heap of boxes: clothes and miscellany in cardboard, to be delivered first thing in the morning. Renovictions were devouring the hungry city: stone facades and steel spines gentrified whole neighborhoods, creating towering fortifications against the increasing number of poor and unhoused people. It was her second time being uprooted in a year continuously marked by false starts and endings. In February, a miscarriage; a breakup in June. She crawled through the months in the detritus of her imagined future. To desire is to mourn, she’d written in her journal on a snowy morning, her handwriting foreign, girlishly big and shaky. She’d felt maudlin and grew red-cheeked even as the truth of both her desire and her mourning gnawed at her bones. The feeling—of emptiness, of ruin, of impossibility—stayed inside her, no matter what she did.

It had been sheer luck, or a turn of it, maybe, that she’d needed a place just as her auntie Deb was moving back to town; even luckier that Deb had found a whole house to rent at the edge of the city. The bus route ended just outside the small two-story home; black silhouettes of trees behind the property snarled up at the light pollution. Cece often thought about how her ancestors might have lived on the land before the city stretched and sprawled out over the coastline. The bones of those distant family members were, she knew, interred in the soil, some beneath the since-closed downtown library, smothered by its concrete. She tried to feel connected to them in each moment, learning the traditional calendar, noticing when sap poured from bark on the trees and the fireflies blinked their Morse code into backyards and the too-tall grass of abandoned lots. The connection felt good: a way to mitigate the alien chaos of the city, the place that screeched and menaced you with its strange machinery. It was nice, for once, to be at its edge instead of in its mouth.

A new life: so came this first night in the chrysalis of the empty house. Each room contained the ghosts of future memories. Aunt Deb would for sure put her cousin’s photos up on the wall alongside kitschy Jesus artifacts and a patchwork quilt or two. Cece roamed from the empty living room to the kitchen, imagining their near future in the home. There would be dinner parties, board games, visits with friends. Maybe she could plant a garden. She knew better than to envision any further: the future was a room with a warp in the floor. It was a dangerous thing to think or speak into being, like a too-early pregnancy announcement.

“I don’t mean any harm,” she said to the house. “I just live here now. First-night jitters.”

She laughed to herself and the air felt lighter. It was a roof over her head. It was the best she could do for now and that could be good enough.

At the bottom of the stairs, a smell of blood: the wet metallic cling slapped her across the face, followed by a waft of rotten meat. Rustling sounded in the walls. Why had there been a doll? Her mind raced. A doll: apsute’gan.

“Apsute’gan.” Her nukumij’s soft fingers made the doll dance. Cece reached for the doll and her grandmother pulled it gently away, her eyes imploring and focused on hers. “In Mi’kmaw, tu’s: apsute’gan.”

Cece repeated it and grasped the doll from her grandmother’s hand. She made the doll dance, like her nukumij had. “Apsute’gan,” she repeated once more in a singsong voice, and skipped out of the room.

The little doll, Rosie, had been her favorite: woven by one of her nukumij’s friends. It was so unlike her other dolls, which were all white porcelain or brown plastic and wearing fussy dresses of shining satin and coarse lace. None of them quite looked like her, though she’d loved them all the same. She spent many afternoons healing their invented wounds and tried to be a nurturing mother, imitating the actions of care: invisible meals and pretend outings and real tea parties with luski on rose-lined plates.

This doll had been left behind by a child. Of course. She’d had a night terror that included the woman singing and it was juxtaposed with the doll that was left behind. A coincidence. Cece’s knees shook as she closed her eyes and demanded that she accept it as the truth. Children made dolls all the time. She’d made her own, she’d made potions and strange concoctions and effigies in the woods her whole life. It was just for play, to imitate a mother, to feel less lonely as each friendless afternoon stretched before her. The doll was such an easy way to feel like she belonged to something, that something belonged to her.

She didn’t know if she could get back to sleep. She sat on the floor of the living room, watching the streetlights make the trees, and their shadows, dance on the walls. Sleep found her again.

A singsong voice clamored into her thoughts. Fungi sprouted from the walls with many fingers, rustling like paper, an atonal music box tinkling: Dead man’s fingers break down the trees. Dead man’s fingers crawl over me.

Cece woke again, body tight with panic. Her eyes focused on the window once more. She tried to calm herself: Breath in. Hold. Breath out. Watch how the lights outside make shadows on the floor. It was just another nightmare.

She blinked back tears as she struggled to steady her breath. She didn’t have enough money for a hotel. She didn’t have a car to sleep in. She was stuck alone in the house with nothing until morning. She stretched with a sharp ache in her side and tried to ignore the vomit curdling in her stomach, begging to be announced. The strange smells of blood and meat had vanished: they, too, may have been remnants from the edges of sleep.

She needed a distraction. She’d left her laptop upstairs. Dread beading sweat at her brow, Cece climbed, staring only at each stair as she went, unable to meet the gaze of the dark walls.

The top of the stair felt darker than before: the center of a collapsing star. A rustling was coming from the bedroom across the hall once again.

Cece ignored it and opened her bedroom door. She stepped inside. Nothing strange. Relief coursed through her. With a trembling hand she placed the lantern on the floor. She picked up her laptop and tried to turn it on.

Nothing. Cece placed it back down and grabbed her cell phone.

Nothing. She groaned in aggravation.

A woman’s voice started singing again: faint and growing louder.

Cece dropped her phone and whirled around.

A woman stared through her with two voidblack eyes, screaming sockets howling emptiness and death.

Cece screamed. She couldn’t resist her tears any longer. She ran for the door; it slammed shut. She pulled at the handle. The door would not move.

“Get out,” the woman hissed.

“What is your problem, aqalasie’w? I’m trying to!” Cece yelled.

“My husband built this house.” Each word hissed between the woman’s stained and broken teeth. “This has always been my house.” Her corpse-pale skin glowed dimly in the dark.

The woman blinked out of sight in an instant, and Cece began to sob. She tried again to open the bedroom door but the knob still would not move. She ran and tried to pull up the window but it was painted shut.

The house was breathing: the wallpaper shifted redpink in the soft light of her lantern. The curlicues on the pattern glistened and moved in a wet rhythm, becoming organs producing life, carrying blood and oxygen through the digestive system of the house.

The house is living. The house is watching. The house desires.

She pressed her hand against the wet wall, the slippery glisten of organs pushing back against her bare palm, sponge soft. She tried not to retch.

“Please,” she screamed, “you want me to leave. I’ll go. Please let me go. I’ll never bother you again. I’ll make sure my auntie doesn’t move in, either.”

Blood pooled in her mouth. The woman started singing as everything went black.

In the dark room the dollhouse burned jack-o’-lantern bright; its tiny bulbs cast orange shadows on its wooden walls. The house was her aunt’s house: this new old place at the end of the line. A dollhouse the miniature of where she stood: a more comprehensible place, with walls that did not breathe and molder and change. A rustling sound came from within its walls. Cece peered closer.

In the bed a moth twitched and writhed. Its limbs kicked helplessly at the cold air, its wings thrashing with a dull thud against the tiny wooden bed frame.

“Don’t worry,” the woman cooed at Cece. Strands of her silver hair glinted in the lamplight. “We’re going to make everything just right.”

Head surging with pain and confusion, Cece turned to look in the direction of something she could feel looking at her. A little girl rocked silently on a chair, staring at Cece with wide doll eyes. Her dress had an unnatural satin gleam in the moonlight; her glassy eyelids blinked, rolled open, blinked, rolled open as she rocked back and forth on the chair.

“We told you to leave,” the girl hissed. “But you didn’t do it. Now you will become my doll.”

Her snarling mouth stretched into a terrible distended smile.

“Yes. My little Indian doll.”

Cece’s gaze turned back to the dollhouse and to the small furniture in the room, getting smaller alongside her. All of it was warm and welcoming; it would be lovely once they were hers, wouldn’t it? She could have that home of her own. Perfect tiny wooden oven, small Christmas light bulb buzzing, the whole house lit up pristine and warmbright as a happy memory, this new world of hers, this more inhabitable microcosm without floods and forest fires and collapsing bridges and late nights at work. Of course, she would need a poseable arm to get around and perhaps a bendable knee. She tried to smile at the thought, but her face did not cooperate. Her body was becoming stiff, growing harder and thinner and colder, more delicate, porcelain painted in a deep shade of sienna, darker and more beautiful than she’d ever been, she realized, more perfect in the woman’s image of her, more authentic, more believably real—

The maggot singing rot dripped from the ceiling and onto the floor. Flies buzzed at the windows, snails hatched and crawled forth onto the floors, leaving trails of slime across her body, multiplying, and writhing in time to the mother and child’s hymns and nursery rhymes, tinkling music box lullabies—

She could be a perfect little doll. Pain thrummed between her temples again. “Apsute’gan,” Cece mumbled. The word resounded in the dark.

Her grandmother’s voice cut through the dark.

“Tu’s.”

Something shook her arm.

“Tu’s.”

Fear shot Cece onto uncertain legs: she was no longer able to blink. Rage coursed whitehot in her stiff body as she shambled forward, knocking the dollhouse to the ground. The woman and child screeched in unison. A gust of wind knocked Cece backward onto the floor. Her porcelain hand howled open and shattered and she felt nothing, just the rage of becoming, the rage of undoing, the promise, under it, of what she could build in its ruins.

She clambered over the maggots, feeling them writhe and smash under her still-fleshed arms, crawling to the dollhouse. She threw what was left of her weight on top of it, her shoulder breaking and splintering the tiny furniture. In the sounds of music box melodies were melting screams and shattering glass.

The floor began to shake as the house quivered its death rattle. The writhing walls stopped breathing. The maggots and snails disappeared.

Cece opened her eyes—she hadn’t realized they’d been closed. The room had returned to a comprehensible layout. She held her aching fingers to her face and smiled as they began to move. She sat up with a deep and grateful breath in her body, her home. Sunrise creaked through the window with the sound of birds.

Tiffany Morris is a Mi’kmaw writer of speculative fiction and poetry from Kjipuktuk (Halifax), Nova Scotia. Her work has appeared in Nightmare magazine, Apex Magazine, and Uncanny magazine, among others. Her full-length horror poetry collection is Elegies of Rotting Stars. Find her online at tiffmorris.com or on Twitter @tiffmorris.

“Night in the Chrysalis” by Tiffany Morris, originally collected in Never Whistle at Night (Vintage Books, 2023). Copyright © 2023 by Tiffany Morris.

Published by arrangement with Vintage, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Edited by Shane Hawk and Theodore C.Van Alst Jr., Never Whistle at Night: An Indigenous Dark Fiction Anthology will release September 19. You can pre-order a copy here.

Want more io9 news? Check out when to expect the latest Marvel, Star Wars, and Star Trek releases, what’s next for the DC Universe on film and TV, and everything you need to know about the future of Doctor Who.